From June 1 to Nov. 30, it’s hurricane season for the U.S. Atlantic Coast. But this year, coastal communities are facing a double threat to their health and safety during the COVID-19 outbreak.

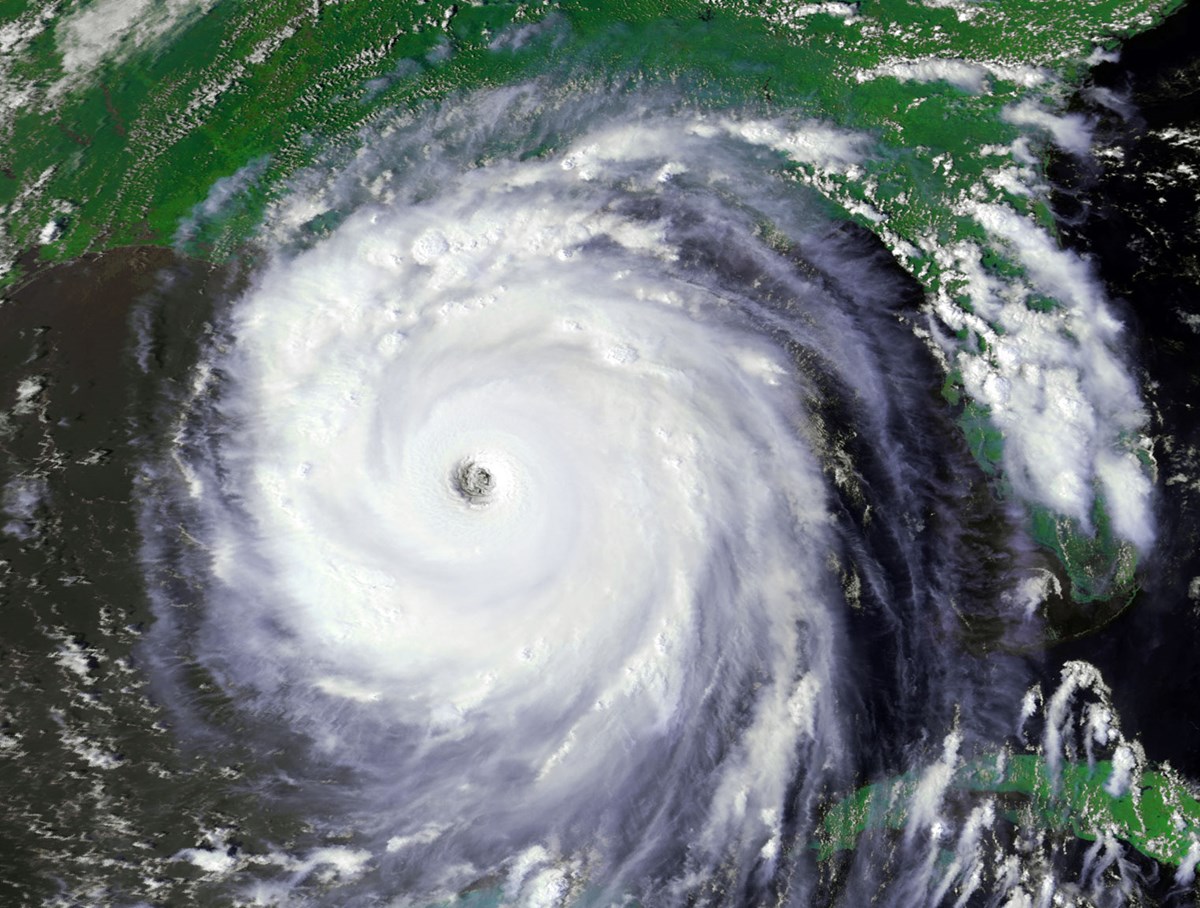

If a Katrina-sized (or larger) hurricane were to strike anywhere from New Orleans to New York during the pandemic, communities along the coast would be given a few days to evacuate in massive hordes. Social distancing would become irrelevant and infection rates would soar in mass shelters like the Superdome. Where would evacuees go? How would they protect themselves from a storm and a virus?

“It would be catastrophic,” said coastal Louisiana resident and Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw tribal member Chris Brunet. “How do you begin putting together a response for that?”

Brunet lives and grew up on Isle de Jean Charles, an island in the bayous of South Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana. Though the Louisiana Department of Health reported just under 500 cases of COVID-19 in Terrebonne Parish, Brunet and his family have kept a safe distance. While schools and stores remain closed for public health, Brunet said he doesn’t feel worried about leaving his house on the isle because the community is so isolated itself.

“The people are not close together as you would see in a city—it’s mainly us,” said Brunet.

But the real hub of the virus is about 80 miles northeast in New Orleans, with high transmission rates traced back to late February’s Mardi Gras crowds. By the beginning of May, the city confirmed more than 6,000 cases and early forecasts are predicting a busy hurricane season.

John W. Day Jr., an emeritus professor of oceanography and coastal science at Louisiana State University, said “it’s not a new problem, but I think the intensity and magnitude of it is what’s going to change.”

The Gulf Coast is projected to see larger hurricanes more frequently, according to his research, where more Category 4 and 5 hurricanes are expected to be more intense and move slowly over larger areas.

“If a storm can intensify that quickly into a Category 5 hurricane, there’s not time for people to leave the city—it takes more than two days to evacuate,” said Day. “There’s a real sense of foreboding. The impacts are a part of real life from now on and it’s just going to get worse.”

In April, Gov. John Bel Edwards ordered state agencies to prepare emergency guidelines to accommodate an evacuation order during the pandemic. Updated hurricane evacuation guidelines include social distancing regulations in shared shelters and public transportation. Evacuees awaiting transportation to a shelter will be provided a mask and screened for symptoms at Evacuspots, while those with a temperature more than 100 degrees will be isolated.

Similar emergency plans are under construction along the Atlantic Coast to keep populations safe from both storms and the virus. In New York City, which took about $19 billion in damages from 2012’s Hurricane Sandy, the pandemic has delayed progress on major resilience projects like sea walls. The question of preparedness has now forced major cities to rethink their emergency plans and to respond to the COVID-19 crisis.

“Nobody can be spared from this pandemic; not the smallest community or the largest—then add the uncertainty of a hurricane for the Gulf or Atlantic Coast communities,” said Brunet. “As hurricane season gets closer, you hope that storms hold back. And if anybody does get anything, you hope it’s not too severe.”

For Miami Beach, a city threatened by frequent gulf flooding and sustained by a currently floundering tourism industry, COVID-19 has been detrimental to the economy. Climate resilience projects like elevating roads and installing new pumping infrastructure have been set aside while the city funnels its resources into COVID-19 response efforts.

“Look how quick it changed,” said Brunet. “It just makes you think that no matter how prepared you think we are something can destroy us. Katrina was the storm that should have never happened, but everybody knew that one day it was going to happen.”

Last summer, Hurricane Barry reached the Isle de Jean Charles in late July right before the start of the school year. Brunet hopes that “we don’t get no hits,” but if they do, they may be better equipped to handle an emergency once the virus recedes.

Outside of Brunet’s home, raised on stilts to avoid floodwater, is a repurposed toilet displaying a sign; “climate change is not worth___.” Though the island is subject to frequent flooding and shoreline erosion, Brunet said he feels climate change is only a small part of the problem.

Now, he is considering swapping out his iconic commode for a new symbol this season: a roll of toilet paper. “When the pandemic took over the climate change talk, the community was looking for toilet paper,” said Brunet.