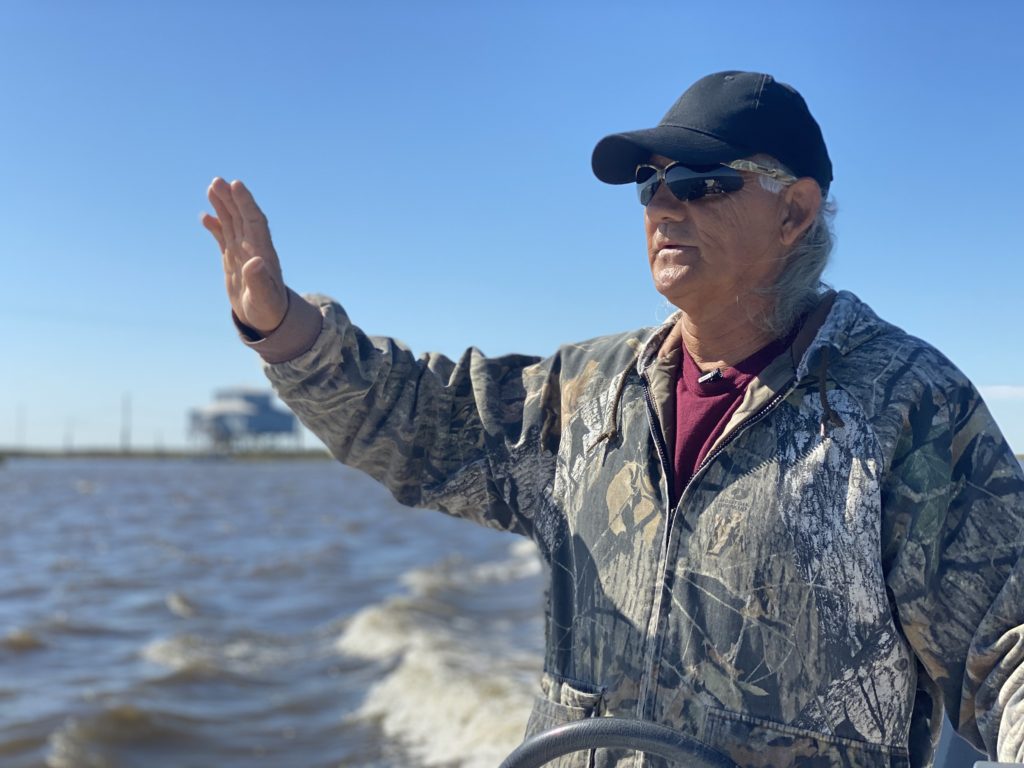

The sun seems to love the skin on Donald Dardar; his skin is warm bronze with sunspots and deep lines. His face is weathered; he has the look of a true captain. And when he’s out on his boat, his skin gleams, and his long silver hair blows in the wind behind him. The sun’s reflection on the water causes Dardar to wear his cool shades with golden frames, but if you’re lucky, you’ll get to his hazel eyes sparkle in the sun as they fix on the stretched landscape of dead trees and narrow water ways.

Dardar is a member of the Pointe-Au-Chien Indian Tribe that shared the bayous of South Terrebonne Parish La. with another tribe, Isle de Jean Charles Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe. Throughout the parish are canals and Dardar frequently takes guests of the Tribe’s visitor center out on his boat. But the boat rides are only part of the experience. Dardar’s boat is a time machine. He takes you on a journey through time, recollecting the time when the bayous and canals that crisscross the Mississippi River Delta in Terrebonne Parish were once filled with houses where he grew up.

What was once a robust community of Native Americans who thrived on the land they lived on through fishing, farming and strong family ties, is now mostly marsh for the Pointe-Au-Chien Tribe. The land Dardar grew up on is just a memory and is now replaced with spindly dead trees, thin strips of land that peak through the high waters, and eye-sore signs that say, ‘Warning – Do Not Anchor or Dredge Crude Oil Pipeline Crossing.’

Amongst the desolate water ways are gems, and luckily Dardar knows just where to find them. Because Dardar grew up navigating the water with his father, and still goes out frequently, he knows the maze of canals by heart. Like he knows the back of his hand, Dardar steers the boat to a beautiful, bright orange tree grove that looks like it belongs in The Wizard of Oz and not on a dying strip of land surrounded by dying trees. The only sign of thriving greenery on the ride, has bigger than palm-sized oranges that actually taste like lemons. And if by chance, the weather is right and Dardar navigates skillfully -as he always does- you’ll get to see a couple bottlenose dolphins playing through the canals and circling the boat.

But, neighboring the now marsh, that the Pointe-Au-Chien Indian Tribe use to occupy, is another vanishing community. In fact, it’s a vanishing island. Isle de Jean Charles, home to the Isle de Jean Charles Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe, is a sinking and eroding land that is still trying to survive the water surrounding it. And not only is the land clinging on, so are the people who inhabit it.

The Isle de Jean Charles Tribe are descendants of three historic tribes that fled the bayou, hoping to avoid forced relocation by Indian Removal Act in 1830. Now in a similar situation again, members of the tribe have to leave their homeland, not escaping persecution, but the climate that is eating away their ancestral land.

According to the Natural Resources Defense Council, the state of Louisiana loses about a football field’s, 2,000 square miles, worth of land by the hour. According to a NASA study, New Orleans, including the Upper and Lower 9th Ward, the land is sinking up to 2 inchers per year. Now Orleans’ Lower 9th Ward, somewhat an island of its own, is still recovering from the devastating Hurricane Katrina and is now facing more climate issues with coastal erosion.

In the United States, coastal erosion from rising sea levels has been on the rise. According to the U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit, the United States lost an area of wetlands larger than the state of Rhode Island between 1998 and 2009.

Globally, the sea level has rising as well. Over the past century, global sea level has risen; in 2014, global sea level was 2.6 inches above the 1993 average— which was the highest annual average in the satellite record. Sea level continues to rise at a rate of about one-eighth of an inch per year, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Isle de Jean Charles has shrunk 98% since 1955. Due to a number of climate-related issues like rising sea levels, erosion, and hurricane damage, the people on the island are once again having to pick-up their lives to relocate, leaving the land paramount to their culture.

The people of Isle de Jean Charles, natives and non-natives, have been coined America’s first ‘climate refugees,’ by the New York Times, but that doesn’t sit well with residents. The term ‘refugee’ is used for people crossing international boarders seeking asylum, this isn’t the case for the Isle de Jean Charles residents. Cookie Naquin, niece of the Chief Albert Naquin, says she doesn’t care for the term.

I’d rather not be called that [refugee],” Naquin said. “I’m human just like them.”

Once diligent fishermen and farmers, the land provided for the tribe and shaped their very lives and is the epicenter of their culture. Tribal Chief Albert Naquin, whose ancestors, Jean Marie Naquin and Pauline Verdin, founded the island, distinctively remembers his tribe living off the land. His mother and aunts would garden tall okra plants, peas, tomatoes and beans and would all cook together. His father and uncles would fish for trout and farm, raising cows and pigs. They were a community that lived off the land and shared everything, keeping family ties strong.

All of that has changed now. Families have moved off the island, most of the island has disappeared, and because of the saltwater intrusion fishing and gardening is no longer done on the island.

“It’s like night and day,” said Chief Naquin. “We used to walk on both sides, used to see the land, see grass. Where we use to walk, we use boats now.”

Chief Naquin remembers running through water on the island as a child, but now, things are much different.

The only way on and off the island is a narrow, water-eroded road built in 1953 through the past marshland that has since been washed away. Island Road is prone to flooding during tropical storms, high tides and even strong winds that push the current. Consequently, most islanders have high, rusty pick-up trucks to make sure they can leave, or get to the island during inclement weather.

Now, the island houses less than 20 families and a couple fishing camps. The families remaining are nothing but resilient. Most of the remaining homes on the island are abandoned, decaying from past hurricanes or sit tens of feet in the air, towering over what used to be. The homes that are still there are islanders who do not want to give in to the resettlement proposed by the government. The remaining families don’t plan on moving off the island anytime soon and have “Not for Sale,” signs in their yards to prove it.

In 2016, a $48 million “climate resilience” grant from the Department of Housing and Urban Development was set aside to resettle the residents of Isle de Jean Charles. This was the first allocation of federal tax dollars to move an entire community battling climate change. The resettlement of the community has been a heart-breaking and frustrating situation for the residents.

“It’s like someone pulling your heart out,” said Naquin.

Scott Hemmerling, director of Human Dimensions at the Water Institute of the Golf, said that the tribe will suffer from the resettle efforts.

“How do you just move a culture?” Hemmerling said.

The resettlement was originally to take place in 2016 but was given an extension to 2020. An old sugarcane plantation was purchased for the residents and new homes were to be built. Unfortunately, still no houses have been built yet. For the island residents who sold their homes and were told they’d be moving into the new ones on the purchased land, life has been moving from place-to-place waiting for their new community to be built.

“You’ve got almost $49 million that the state has had for four years, and nothing has been done,” said island resident Johnny Tamplet.

The land itself is vastly different than the island. The sugarcane field is sandwiched between two very busy highways with very little greenery and certainly not near any waterways. If to move there, residents would be giving up their homes, their land, and their heritage.

Construction on the 515-acres of land located just of LA 24 next to the Gulf of Mexico Chevron Preservation and Maintenance Facility was supposed to start in March of 2016, but when we visited the area in early March of 2020, the field was still just that, a dirt field more suitable for farming than establishing a community of people.

The story of the island tribe

The mistreatment of Native Americans is nothing new, and especially for this tribe. From the Trail of Tears, to the Indian Removal Act, up to now in 2020, the Isle de Jean Charles Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe has been counted out.

Like the blood flowing through their veins, so does their tribe’s roots roam through the island’s land. The natives of the Terrebonne and Lafourche Parishes in Louisiana were people from five different tribes- the Biloxi, Chitimacha, Choctaw, Acolapissa, and Attakapas. They all came together in the 1790’s, but the majority were from the Chitimacha tribe and were believed to be there before the arrival of Europeans, according to the Daily Advertiser La. newspaper.

Simultaneously in 1785, Frenchman Jean Charles Naquin arrived in Louisiana aboard the Le Saint-Remi, fourth of seven ships carrying Acadians that were exiled from Canada. He and his wife Marie Madeleine Gabriel Laboeuf settle into Platttenvile Louisiana, giving birth to Jean Marie Naquin and three other children

In the 1830’s President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act ordering the forced removal of Natives from their land in southern states. Both from the Indian Removal Act and the Trail of Tears, some Natives fled to the deeper bayous of Louisiana. Naquin married an Indian woman, Pauline Verdin, whose family fled to the bayou. Naquin and Verdin moved to a strip of marsh that would soon be named after his father, and what we know today as Isle de Jean Charles, according to the Tribe’s website. All of their children, except one, married into Indian families and began to interweave their cultures, speaking a hybrid of French and their Native languages, some that is still used today by their Chief and older tribal members.

By 1880, the Terrebonne Parish Census listed four families as island residents’ the male household heads were: Walker Lovell, Jean Baptise Narcisse Naquin, Antoine Livaudais Dardar and Marceline Duchils Naquin. To this day, some of the Dardars and Naquins still live on the island.

At the island’s peak, about 300 families lived on the island. Men were fishermen, farmers and oystermen, together creating strong family ties and sense of community.

“The women would clean the meat, that was their role,” said Chief Naquin, recalling the island from his childhood. “They’d have big garden and grow okra, cantaloupe and butter beans.”

“The women would clean the meat, that was their role,” said Chief Naquin, recalling the island from his childhood. “They’d have big garden and grow okra, cantaloupe and butter beans.”

According to Chief Naquin, there was so much greenery and animals on the island that they never went without. On Sundays Chief Naquin said everyone would go house-to-house after cooking, eating and just enjoying each other’s company. According to Naquin, their tribe didn’t have Native American Traditions, like sweat lodges like other tribes; theirs was more family centered.

“We would go visit everyone every Sunday,” he said. “You’d stop for a cup of coffee and just sit there and talk. There would maybe be about 20 that would meet. The kids would wrestle, play around. Men fix houses that needed help.”

The island was the piece that held the tribe together, and now it’s slipping through their fingers. Cookie Naquin, niece of Chief Naquin, also grew up on the island. Cookie is a jokester and loves to light-hearted sarcastic nods. What she doesn’t joke about is her home and the island. Like others who grew up, living off the land is what she remembers most vividly, and she says that oil companies and their dredging, are taking that away from her.

“I was raised here, it means my entire livelihood,” said Naquin. “I used to go fishing, and now I can’t, the oil companies are the reason.”

Life on the island was a dream. And now, the island much like a dream is becoming a distant memory. There are few houses, and all raised at least 10 feet in the air to combat flooding. There are rusted cars and appliances sitting in fields like old statues. Right when you get to the islands, stand just a metal frame of a house that was destroyed in a past hurricane, and around it, the grass and weeds stand tall. There are no longer the gardens Naquin mentioned and there aren’t any farm animals in sight.

Now, there are less than 20 families on the island. Between dredging, and climate change, it has been increasingly more difficult to live on the island. Voluntarily, families have moved away, sold their homes and are awaiting their new homes promised in the resettlement agreement.

The resettlement of the Isle de Jean Charles residents is much like entering the twilight zone for its past residents. The Louisiana Office of Community Developed spent $11.7 million on a 515-acre on an old sugarcane plantation to relocate about 80 residents from the island. A hefty price tag on such a cultureless strip.

In the field you can hear cars going on the adjacent freeways and not the sound of birds or waves. You can see the big Chevron facility and street signs, not trees and the orange sunset against the water’s edge. The field is just a field and will never match the island’s beauty or cultural significance to the tribe.

Things would be slightly different, according to Chief Naquin, if the tribe had money. There are 10 state-recognized tribes and only four federally recognized tribes in Louisiana. The Isle de Jean Charles Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe is state-recognized but not federally recognized, so in that aspect they miss out on federal dollars to help their members. Chief Naquin says the tribe is missing birth certificates from some great-great family members, making it difficult to be a stand-alone tribe.

It’s been an uphill battle for Chief Naquin. He says that because he’s chief, he takes all the heat. When he goes to state and federal meetings, not many tribal members show up. Because most tribal members work, their schedules don’t allow them to help Chief Naquin as much as he’d like.

“I always get the blame for everything,” he said. ”I fight with the state, with the parish, and I’m always alone. People never show up.”

He said he thinks his people have stopped trying.

“If you send for troops out of war and only the general shows up, you get a beating,” he said.

But Chief Naquin isn’t ready to give up yet. He said his tribe needs a community. He wants to see the “young folks” grow up the way he used to. He would like his family to get back together and the way to do that, is become federally recognized and get help.

The Director of Office of Indian Affairs for Louisiana Pat Arnold has been researching the tribe’s resettlement and conducting property surveys of the new land. She noted that if residents signed for the total relocation, they could never return back to the island. She said that the deal between the residents and the government is “unfair.”

“It was like giving away their rights to the property they had lived on all their lives,” said Arnold.

In 2001, the United States Army Corps of Engineers built a 72-mile levee system called the Morganza to the Gulf of Mexico Hurricane Project. It was designed to provide hurricane protection to the Terrebonne and Lafourche Parishes. According to Jerome Zeringue, who was the director of the Terrebonne Levee and Conservation District, the Morganza would only be leaving out a few people. And those people, were the residents of Isle de Jean Charles. According to the tribe, in 1998 the Army Corps of Engineers decided it was not cost-effective to include the tiny island. They decided the people living on the island were not worth the time, effort or money.

“An argument to have built the Morganza system to include Isle de Jean Charles in the protection system based on the value of the human lives and culture on the island, but the Army Corps of Engineers must have done a cost-benefit analysis in which they found the cost of including the island was not worth the benefit,” said Director of Costal Restoration and Preservation in Terrebonne Parish Mart Black.

And that is just what the government did. They bought out the people and are forcing them to a not-built-yet community that is polar opposite to the land they call home.

Vanishing coasts

Vanishing coastlines isn’t just a problem for Isle de Jean Charles, but for the entire state of Louisiana. Restore the Mississippi River Delta, a coalition of the Environmental Defense Fund, National Audubon Society, the National Wildlife Federation, Coalition to Restore Coastal Louisiana and Lake Pontchartrain Basin Foundation, have been working to rebuild costal Louisiana. According to the coalition, since the 1930’s, Louisiana has lost over 2,000 square miles, an area almost the size of Delaware.

“Climate change has been going on for a long time,” said Director of Costal Restoration and Preservation in Terrebonne Parish Mart Black. “It’s just that we have gotten to point where we can effectively measure it.”

Scientists have measured it, but locals across Louisiana say they’ve seen it. Jackie Usaie, Louisiana native and mother of a charter fisherman, goes out with her son fishing occasionally. From growing up in Louisiana to now, she said she’s seen the change. Sitting at a table with her husband in Bayou Cane Seafood, local restaurant in Houma, she recalled Louisiana’s landscape and seafood culture.

While finishing up her food Jackie said, “There’s nowhere else in the world where you can’t find food in a ditch.”

And looking at the mound of crawfish carcasses on top of the table, she was correct. She emphasized that she and her husband do not believe in climate change, saying the weather has always been the same, however, she does see a difference when out fishing.

“There’s a big difference in the coastline, you see a lot more water,” she said.

Her husband also has seen a change in the amount of water on the coast, but attributes its rise to the oil companies, not climate change.

“There’s no change in the level of the sea because of climate change, it’s from the buffering and fracking and erosion,” Reggie Redmond Sr. said.

The coastline aren’t the only places disappearing. Louisiana’s swamps and marshes are also being affected. Richard Brunet, born and raised in the bayou of Houma Louisiana calls himself, a “coonass.” The term, to some, is a controversial ethnic slur for the word ‘Cajun,’ to others, it’s a badge of pride that showcases southern Louisiana heritage. For Brunet, it’s the latter.

“It’s actually [means] the people from the bayou who are used to living off land and water,” said Brunet.

Brunet is a Cajun if there ever was one. He has a molasses accent that pours through his words with a southern drag. He fishes for crawfish, hunts, and on the occasion, wrestles alligators. Brunet said he and his teenage boys go fishing and looking deep in the swamps for “whatever comes out.” To him, swamp culture is everything and he says it has changed since he was a little boy. He said some of his favorite spots are so high with water that he can’t camp there anymore and that the swamps are getting smaller.

“It’s slowly eroding, the Mississippi river and all the water coming from up north from the snow, isn’t helping.”

After levees were placed on the Mississippi in Louisiana with the intention to stop excess water from hurricanes, an unintentional affect has become a result. Since water is being blocked, so is the sediment it would normally bring along with it. Consequently, land loss from erosion isn’t being replaced with new sediment and fresh water from the river isn’t slowing down the erosion from the saltwater. These two factors are some of Isle de Jean Charles’ biggest issues.

Isle de Jean Charles is experiencing a lot. High tides are causing flooding, fracking and dredging of nearby canals are possibly causing land loss, the levee on the Mississippi river is causing land loss due to its inability to replace settlement. The sinking of the island (or rising of the water, or both) isn’t a one solution fix; it may not be fixable at all.

“Right now, it’s too late to save the island. It’s too little, too late,” said Rita Falgout, cousin of Chief Naquin.

Falgout is 83 years old. In 2018 she made the hard decision to leave her house on the island behind and accept the resettlement proposal in the new area. Because no houses have been built yet, she’s had to move three times since then.

Falgout said they had to move in fear she and her husband would not be able to leave in case of emergencies. Island Rd., the only way to and off of the island floods frequently. And with more frequent flooding, it’s been increasingly difficult to navigate to and from the island.

“Too much water,” she said. “My husband was sick, and we didn’t have transportation and I was worried about him, something happening, him getting worse or something and we’d have an emergency. And I said, ‘What do we want to do here? What if the road is flooded?’ I said, ‘He’s not going to ride in a helicopter.’”

Unfortunately, Falgout’s husband passed away before he could see their new home. Now, still waiting on its construction, Falgout still hopes to see her family in friends in their new community.

From coastal areas, to swamps and to the Isle de Jean Charles, Louisiana’s land has been changing for some time now. People across the state are seeing the change and lives are being affected. Land is diminishing and if not dealt with quickly and effectively, Isle de Jean Charles won’t be the only part of Louisiana to disappear.

New Orleans

New Orleans is completely different than the rest of the state. Rural meets urban, Cajun meet Creole and jazz, food and culture mix into a big pot of gumbo, giving you a taste of everything southern. But buried in the muffles of trumpets, big bands and parades is a place that has also been forgotten and ignored by Louisiana’s government.

Much like an island of its own, the Lower Ninth Ward, the hardest area hit by Hurricane Katrina, also a predominately black neighborhood, has still yet to fully recover. The Ninth Ward, 15 years after Katrina, still has unoccupied, decaying houses. Many are remnants of destroyed houses or boarded up with “no trespassing” signs. There are many overgrown lots where houses once stood with grass and weeds that are at least mid-calf height. One person stated that they mow the grass in the open field across the street to prevent people from sneaking through it.

Victims of crime, poverty and racial disparity, it seems that Louisiana has turned a blind eye to people of the Ninth Ward. According to the Data Center, almost 25% of the percent of total households reported less than $10,000 or less from 2014-2018 and the average household income to be a little over $33,000. The people of the Ninth Ward are still struggling with Katrina’s wrath and their poverty-stricken area hasn’t gotten much help since then.

Nevil Brown, a Lower Ninth Ward resident, was one of the lucky ones when Katrina hit. He had left two days prior to Missouri and stayed during the storm. Brown wasn’t able to get back to the area for another 2-3 months before he was able to return. After getting back, he said nearly everything had been destroyed.

He also said that the government didn’t really provide any help after the hurricane. The community is still waiting for something from them.

“[It’s] really hurtful,” said Brown. “The government never gave me nothing.”

Lower Ninth Ward Firefighter Jimmie Harris was fortunate to have had flood insurance and received a little help. Harris’ house flooded with about 8ft of water and he and his family had to evacuate.

After returning, he said there was debris and about three inches of mud in the streets.

“It had this raw, sewer-like smell,” he said. “It was a mess.”

When the water resided and he returned home, he said everything had floated towards his front door. He said it took him three years to rebuild.

“The community tried to help each other, but everybody needed help,” said Harris. ‘It was kind of everybody on their own—it took longer for us to get back up on our feet.”

And some residents are still fighting to get back on their feet. Jerry Gibson has lived in New Orleans for over 60 years and was home when the water started to rush in. Gibson said he was asleep when water poured into his bedroom. In an instant, his whole house was flooded; he thought quick and escaped out of the kitchen window to the roof of the house.

The water was high, and the current carried him away in an instant. Luckily, there was a tall palm tree down the block he clung on to. He said the storm ravaged, he saw neighbors drowning, screaming for help but he couldn’t do anything but hold on.

“It was them, or me,” Gibson said. “I was holding on to the tree while debris was hitting me.”

As quick as the storm arrived, it had left. The furious wind stopped and so did the waves. The bodies of people and animals, debris from houses, all stood still.

“And then the water got calm; the water looked like glass,” he said. “I didn’t see a cat, dog, nothing. It was like a desert ‘round here; it was like I was the only one here.”

Gibson said he knows how to survive. He clung to the tree for about 45 minutes before a crew showed up with a boat and helped him. When he was able to come back to his house, he said only the toilet was left sitting on a slab of concrete, nothing else.

Now, 15 years later, Gibson is still working on his house. When we visited him, he, his brother and a friend were out with plywood and a buzz saw, fixing up the foundation of his house.

Both the residents of Isle de Jean Charles and the Lower Ninth Ward feel abandoned by their government, both state and federal. Each group felt that only the minimum was done to help their plights, and some from both groups hinted at predetermined malice. Either intentional or not, both of these islands are sinking and eroding away both physically and figuratively.

Resilience

Resiliency has been humanity’s crest and for the people of Louisiana, it perfectly describes their plights. For the residents Isle de Jean Charles, although some have moved away and agreed to settle elsewhere, some residents have refused.

Johnny Tamplet, not part of the tribe but a resident on Isle de Jean Charles has no interest in moving whatsoever. His, Cookie Naquin, and a couple other island residents have “House Not For Sale,” signs on their property. For Tamplet, it isn’t about his ancestry running deep on the island that makes him want to stay, it’s the culture and pride of being there.

Tamplet is also opposed to moving for financial reasons. He said he makes less than $13,000 a year. He doesn’t pay a mortgage or property taxes on his home. With the offer of a new home off the island, comes expenses Tamplet isn’t financially ready to pay.

Property tax, house insurance and flood insurance are just some of the bills he would have to budget in if he were to take a resettlement home. And for him, he says “no.” Tamplet isn’t too keen in giving the government his money and he says what he has right now is his and wants to keep it that way.

Tamplet has been very vocal of his opinion, making it known he has no plans to surrender.

“I bought this house 11 years ago in October,” said Tamplet. “And I tell people, I didn’t buy it to live here, I bought it because this is where I wanna’ die.”

The tribe’s resilience rests in the hands of Chief Naquin. And if he can get his tribe federally recognized, he might be able to save the island. If the tribe attains federal recognition, by law, they would be eligible for certain benefits and protections from the federal government. The federal government not only is to provide benefits, financial and others, but to also ensure bargaining power with the Corps of Engineers stating that the island is essential to their culture and heritage.

The people of the Lower Ninth Ward are also soldiers, in surviving a horrific natural disaster and still returning home, trying to rebuild their lives. Like Jerry Gibson, in some way all the resident in Louisiana are clinging to palm trees of their own, hoping for the better and waiting for the storm to pass.

From Bourbon St., to Island Rd., people are making their way through trial and tribulations across Louisiana. With little help, they’ve had to tough it out by themselves and consistently do their best.

Lower Ninth Ward resident Keith Bernard encourages the people of Louisiana not to wait for help, but to go out and seek it. Through all hard work, comes results he said.

“Don’t be a dreamer, fulfill the damn dream.”